This paper approaches the relationship between the Quran and Sunnah from the angle of using the Quranic universals to critique the content (matn) of hadith narrations. Aisha Bint Abu Bakr, the Mother of the Believers, gave us a strong example and a clear illustration for applying this method.

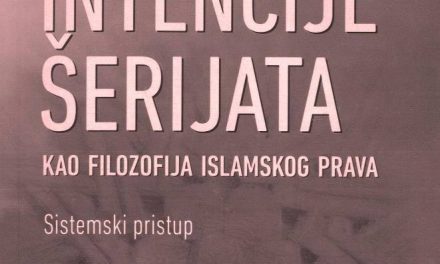

This article will present a number of illustrative examples of hadith, in which Aisha confidently rejected other companions’ narrations, despite being ‘authentic’ according to the sanad verification criteria that had developed later. Aisha’s rejection was based on the contradiction of these narrations with the clear universals of the Quran that revealed the higher principles (usul) and purposes (maqasid) of Islam. This paper will also prove that Aisha’s method is coherent with the classic ‘verification of the content’ (tahqeeq al-matn) method, despite the fact that, historically, this verification was not a common practice. Sunnah in Relation to the Quran Sunnah (literally, tradition) is what is narrated at the authority of the companions about the Prophet’s (pbuh) sayings, actions, or approvals. The Prophet’s (pbuh) witnessing of certain actions without objection is considered an approval from him, by definition. The Sunnah, in relation to the Quran (refer to Chart 1), implies a meaning that is (1) identical to the Quran’s, (2) an explanation or elaboration on a general meaning mentioned in the Quran, (3) a specification of certain conditions for rulings implied in the Quran, (4) an addition of certain constraints to the general expressions of the Quran, or finally, (5) an initiation of independent legislation. Schools of law approve the first three of the above five relations and differ over the last two, as follows. Chart 1. A classification of the possible relationships between the Sunnah and the Quranic verses. If the Quranic expression is ‘general’ and the Sunnah expression is ‘specific’ regarding the same topic, Shafies, Hanfis, Zahiris, Zaidis and Jafaris consider the (single-chained) Sunnah to be ‘specifying’ the general expression of the Quran and, thus, restricting its general expression. Hanafis consider this ‘specification’ to be a sort of invalidation of the ‘confirmed and absolute’ general expression of the Quran and, therefore, reject the single-chained narration that place constraints on the Quran’s general expressions. Malik’s opinion on this issue is to look for supportive evidence to the single-chained hadith that specifies the general meaning of the verse before rejecting it. His additional supportive evidence should be some ˒amal (tradition) of the people of Medina (an evidence which is invalid to all other schools), or a supporting analogy (qiyās). Otherwise, Malik applies weighed preference (tarjīh) and invalidates the single-chained narration. If the hadith implies a ruling that has no relation with the Quran, all schools of law accept it as legislation on condition that it does not fall under actions that are specific to the Prophet (pbuh). Actions specific to the Prophet (pbuh) could be actions exclusive to him out of prophethood considerations or actions that he did out of custom (ādah) of a ‘man living in seventh century’s Arabia.’ Chart 2 shows this classification. Chart 2. Types of Prophetic actions according to their implications on ‘legislation.’ Some Malikis and Hanbalis had added two other types to the Prophet’s (pbuh) actions that do not fall under generally abiding ‘legislation,’ namely, actions ‘out of being a leader’ and actions ‘out of being a judge.’ Al-Qarafi, for example, included all of the Prophetic actions during wars in his ‘leadership actions’, as well as governance-related decisions. He said that identifying the type of the Prophet’s (pbuh) action according to his classification has ‘implications for the law.’ For example, he considered the Prophet’s (pbuh) actions ‘out of being a judge’ to be valid legislations only for judges when they assume their role in courts, rather than for every Muslim. Recently, following al-Qarafi’s example, al-Tahir Ibn Ashur (also from the Maliki school) added other types of actions for ‘specific intents,’ which are meant to imply general and ‘abiding’ legislation, such as, advice, conciliation, discipline, and ‘teaching high ideals’ to specific people. Ibadis include ‘acts of worship’ in actions ‘specific to the Prophet’ (pbuh). These are actions that he (pbuh) did not practice regularly. Other schools of law consider such actions ‘recommended.’ A few Mutazilis differentiated between the Prophet’s (pbuh) ‘acts of worship’ (ibādāt), which they considered the only type that is ‘abiding to all Muslims,’ versus all of his other actions, which they considered matters of ‘worldly judgements’ (mu˒āmalāt). The question of how to differentiate ibādāt from mu˒āmalāt remains an open question, even in the Mutazili theory. The relation between the hadith and the Quran that this article is dealing with does not belong to any of the categories above! It is the case when the hadith contradicts the Quran; not in the explanation, elaboration, specification, addition, or independent legislation sense. It is also the case where the hadith is not addressing an action that is specific to the Prophet, peace be upon him, whether in the legislation sense or the human customary sense. It is the case where the hadith simply contradicts the meanings of the Quran without reservation. The next section will discuss the definition of ‘contradiction’ in the Islamic legal theory. ‘Contradiction’ versus ‘Opposition’ In Islamic juridical theory, there is a differentiation between opposition or disagreement (ta˒āruḍ or ikhtilāf ) and contradiction (tanāquḍ or ta˒anud) of evidences (verses or hadith). Contradiction is defined as ‘a clear logical conclusion of truth and falsehood in the same aspect’ (taqāsum al-ṣidqi wal-kadhib). True contradiction takes the form of a single episode narrated in truly contradicting ways by the same or different narrators. This kind of discrepancy is obviously due to errors in narration related to the memory and/or intentions of one or more of the narrators down the chain of narration. The ‘logical’ conclusion in cases of contradiction is that one of the narrations is inaccurate and should be rejected (perhaps both narrations, if one could prove that). This is the case that this article is dealing with. On the other hand, conflict or disagreement between evidences is defined as an ‘apparent contradiction between evidences in the mind of the scholar’ (ta˒āruḍun fī dhihn al-mujtahid). This means that two seemingly disagreeing (muta˒āriḍ) evidences are not necessarily in contradiction. It is the perception of the jurist that they are in contradiction which can occur as a result of some missing information regarding the evidence’s timing, place, circumstances, or other conditions. Cases of ta˒āruḍ are disagreements between narrations because of, apparently, a missing context, not because of logically contradicting accounts of the same episode. There are three main strategies that jurists defined to deal with these types of disagreements in traditional schools of law: 1. Conciliation (Al-Jam˒): This method is based on a fundamental rule that states that, ‘applying the script is better than disregarding it (i˒māl al-naṣṣi awlā min ihmālih).’ Therefore, a jurist facing two disagreeing narrations should search for a missing condition or context, and attempt to interpret both narrations based on it. 2. Abrogation (Al-Naskh): This method suggests that the later evidence, chronologically speaking, should ‘abrogate’ (juridically annul) the former. This means that when verses disagree, the verse that is (narrated to be) revealed last is considered to be an abrogating evidence (nāsikh) and others to be abrogated (mansūkh). Similarly, when prophetic narrations disagree, the narration that has a later date, if dates are known or could be concluded, should abrogate all other narrations. The vast majority of scholars do not accept that a hadith abrogates a verse of the Quran, even if the hadith were to be chronologically subsequent. This is related to comparing ‘degrees of certainty.’ 3. Elimination (Al-tarjīh): This method suggests endorsing the narration that is ‘most authentic’ and dropping or eliminating other narrations. The ‘eliminating’ narration is called al-riwāyah al-rājiḥah, which literally means the narration that is ‘heavier in the scale.’ Obviously, a hadith cannot eliminate a verse of the Quran. And because the case this article is dealing with is not a case of ‘disagreement’, but rather a case of ‘contradiction’, the above three methods do not apply to our analysis. Degrees of Fame (Shuhrah) of Hadith Valid hadiths are classified into most famous, famous, and single-chained (Chart 3). Most famous narrations are as absolute as the Quran, according to all schools, since they are narrated after a large number of companions (there are various estimates of the number ‘large’), who could not possibly and logically agree to lie. Hadith included in this category are related to Islam’s most famous acts of worship (basic actions of prayers, pilgrimage, and fasting). The most famous narrations are very few. Estimates range from a dozen to eighty narrations. There comprises a category of ‘famous narrations’ narrated by a number of narrators not numerous enough to define it as ‘logically impossible’ for them to agree on lying. This category includes a small number of the hadith available in traditional sources (less than one hundred hadith according to all accounts), which makes its impact on the law limited, from a practical point of view. Chart 3. Types of Prophetic narrations in terms of their number of narrators. The category of hadith which this article is concerned with, and which includes the vast majority of narrations is the āḥād (single-chained) category. All schools of Islamic law, except for some Mutazilis, relied on this type in their derivation of their fiqh. These are narrations conveyed via one or a few ‘chains of narrations,’ usually with slightly different wordings. Verification procedures of āḥād narrators and narrations are detailed extensively in the Sciences of Hadith. The narration has to be valid in terms of its chain of narrators (al-sanad) and its content (al-matn). Trusting a narration’s sanad entails a group of conditions for bearing (haml) or learning the hadith and another group for conveying or narrating (riwayat) the hadith, which all schools agreed upon in principle. For being accepted as a bearer of a hadith, a narrator has to be mature and known to have a reliable memory (al-dabt). For narrating a hadith, a narrator has to be mature, Muslim, pious, has a reliable memory, and has a connected (muttasil) chain of narrators between him/her and the Prophet (pbuh). The exact specifications of each of these conditions are subject to differences of opinion amongst scholars of hadith. The narration has to be valid in terms of its chain of narrators (al-sanad) and its content (al-matn). For the content of a hadith to be acceptable, the main criteria is to be linguistically correct and not to be in ‘opposition’ with another hadith, ‘reason,’ or ‘analogy,’ in a way that cannot be reconciled. However, practically speaking, authenticity of hadith (al-ṣiḥḥah) was judged based on the chain of narrators (al-sanad). Differences of opinion in judging the sanad had implications on the law. Chart 4 summarises basic criteria for accepting sanad and matn. Acceptable narrations by the Zahiris are ‘certain’ and ‘absolute,’ i.e., ‘valid for juridical derivation’ and ‘required for correct belief,’ even if they were single-chained. All other schools consider single-chained narrations to be juridically valid but not part of the Islamic creed. Some Mutazilis differentiate between sayings and actions (including approvals) narrated in hadith. They do not consider actions to be valid evidences of legislation (that are abiding to every Muslim), except in the area of acts of worship (˒ibādat). On the other hand, they consider ‘sayings’ to be valid evidences of legislation in ibādāt as well as mu˒āmalāt (worldly transactions). The question of how to differentiate ibādāt from mu˒āmalāt is another open question. Most schools believed that ibādāt are the issues that ‘cannot be rationalised,’ which also keeps the question open. Chart 4. Conditions for validating single-chains narrations in traditional Sciences of Hadith. Trusting a narration entails a group of conditions for bearing (ḥaml) or learning the hadith and another group for conveying or narrating the hadith, which all schools agreed upon, in principle. For being accepted as a bearer of a hadith, a narrator has to be mature (most estimates for his/her age is seven years old) and known to have a reliable memory (al-ḍabṭ). For narrating a hadith, a narrator has to be mature, Muslim, pious, has a reliable memory, and has a connected (muttaṣil) chain of narrators/teachers between him/her and the Prophet (pbuh). The exact specifications of each of these conditions are subject to many differences of opinion amongst scholars of hadith, even within each school. Moreover, there are clear divisions in terms of trusted narrators between the Sunni schools (Malikis, Shafies, Hanafis, Hanbalis, and Zahiris), and the Shia schools (Jafaris and Zaidis). Ibadis have their own group of trusted narrators as well. The Authentication of the Hadith Content (Al-Matn) Regarding the narrations themselves of the degree aḥād, their content (matn) has to follow the following conditions: (1) The hadith is conveyed in complete and sound sentences. (2) The hadith cannot contradict with other ‘certain’ scripts. (3) The hadith cannot contradict with analogy (according to Malikis, and unless the narrator is considered a ‘faqīh,’ according to Hanafis). (4) The hadith cannot contradict with the narrator’s practices. (5) The hadith cannot contradict with ‘reason’, which al-Ghazali, amongst other jurists, included in the definition of reason, ‘what is acceptable according to common sense and experience.’ Despite the above theories, authenticity of hadith, in practice and especially in today’s scholarship, was judged merely based on the chain of narrators (al-sanad) and not on the matn/content. Today’s scholarship could learn from Aisha’s critique of the matn of some narrations. The following two sections elaborate. Aisha’s Amendments of the Companions Narrations Aisha Bint Abu Bakr (the Mother of the Believers) was a strong, highly learned, and independent woman. Her character showed on a number of her fatāwā and opinions, in which she advocated women’s independence and rights, notably against some of the other companions’ direct narrations. Badruddin al-Zarkashi wrote a book dedicated to Aisha’s critiques to the other companions’ narrations, which he called, ‘˒Ayn al-Iṣābah Fī Istidrāk ˒Ā˓ishah ˒alā al-Ṣaḥābah’ (The Accurate Account on Aisha’s Amendments to the Companions’ Narrations). The following are texts that show examples of these narrations. We will quote and discuss them in order. • في مستدرك الحاكم عن الزهري عن عروة قال بلغ عائشة أن أبا هريرة يقول إن رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم قال: … ولد الزنى شر الثلاثة وأن الميت يعذب ببكاء الحي، فقالت عائشة: رحم الله أبا هريرة أساء سمعا فأساء إجابة … أما قوله ولد الزنى شر الثلاثة فلم يكن الحديث على هذا إنما كان رجل من المنافقين يؤذي رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم فقال من يعذرني من فلان قيل: يا رسول الله إنه مع ما به ولد زنى فقال: هو شر الثلاثة، والله تعالى يقول: (لا تزر وازرة وزر أخرى)، وأما قوله إن الميت يعذب ببكاء الحي فلم يكن الحديث على هذا ولكن رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم مر بدار رجل من اليهود قد مات وأهله يبكون عليه فقال: إنهم ليبكون عليه وإنه ليعذب، والله يقول: (لا يكلف الله نفسا إلا وسعها) – البقرة 285. وفي رواية: قالت عائشة: حسبكم القرآن (لا تزر وازرة وزر أخرى) – المائدة 164 والإسراء 15. In this hadith, Aisha is resorting to the principle universal value in the Shariah, which is justice. She referred the questioner to the Quran that, ‘no bearer of burdens shall be made to bear another’s burden,’ (6:164, and 17:15) and rejected therefore the ‘narrations’ that, ‘the deceased is tortured because of people’s crying after him’, and that ‘the child of adultery is worse than his parents’, etc. Ibn al-Qayyim gave us the following golden rule: Sharī˒ah is based on wisdom and achieving people’s welfare in this life and the afterlife. Sharī˒ah is all about justice, mercy, wisdom, and good. Thus, any ruling that replaces justice with injustice, mercy with its opposite, common good with mischief, or wisdom with nonsense, is a ruling that does not belong to the Sharī˒ah, even if it is claimed to be so according to some interpretation. Thus, no perceived narration or interpretation should ever contradict with justice, mercy, wisdom, or common good. These are the universals (kullīyat) of Islam that should reign over the details (juz˓īyāt). • في مسند أحمد أن رجلين دخلا على عائشة فقالا إن أبا هريرة يحدث أن نبي الله صلى الله عليه وسلم كان يقول: إنما الطيرة في المرأة والدابة والدار، … قالت: والذي أنزل القرآن على أبي القاسم ما هكذا كان يقول الطيرة في المرأة والدابة والدار، ثم قرأت عائشة: (ما أصاب من مصيبة في الأرض ولا في أنفسكم إلا في كتاب من قبل أن نبرأها) – الحديد 22. So, despite Abu Hurairah’s narration that, ‘bad omens are in women, animals, and houses,’ Aisha relied on the Quranic verse that, ‘No calamity can ever befall the earth, and neither your own selves, unless it be [laid down] in Our decree before We bring it into being’ (57:22). This verse, and there are a few similar other verses, set a universal principle that go against the idea of ‘bad omens’ altogether. This is in addition to the other hadith that says, ‘no bad omens in Islam,’ and other similar narrations. Moreover, Aisha narrated in other narrations that the Prophet (pbuh) had said, instead: ‘People during the Days of Ignorance (jāhilīyah) used to say that bad omens are in women, animals, and houses.’ There is another narration where she is saying that Abu Huraira heard the second part of the narration but missed the first part. All these ‘authentic’ narrations are at odds with Anu Huraira’s, which Aisha rejected, not out of mistrust of Abu Huraira, but out of realising the error that he made in the narration. Yet, it is telling that most commentators rejected Aisha’s narration, rather than Abu Huraira’s, even though other ‘authentic’ narrations supported her. Ibn al-Arabi, for example, commented on Aisha’s rejection of the above hadith as follows: ‘What she said is nonsense (qawluha qawlun sāqiṭ). This is rejection of a clear and authentic narration that is narrated through trusted narrators.’ Ibn Al-Arabi’s defence of his sanad-based method of authentication disabled him from showing the appropriate respect for the Mother of Believers in this context! • أخرج الترمذي: قال ابن عباس: رأى محمد ربه، فقالت عائشة: أليس الله يقول (لا تدركه الأبصار وهو يدرك الأبصار) – الأنعام 103. وفي الصحيحين من حديث مسروق: قلت يا أمتاه هل رأى محمد ربه؟ فقالت: لقد قف شعري مما قلت، من حدثك أن محمدا صلى الله عليه وسلم رأى ربه فقد كذب، ثم قرأت: (لا تدركه الأبصار وهو يدرك الأبصار وهو اللطيف الخبير). وفي رواية قالت عائشة: أو لم تسمع أن الله عز وجل يقول: (وما كان لبشر أن يكلمه الله إلا وحيا أو من وراء حجاب أو يرسل رسولا فيوحي بإذنه ما يشاء إنه علي حكيم)؟ – الشورى 51 Again, Aisha is rejecting an authentic ahad narration that the Prophet, peace be upon him, had seen his Lord, based on a Quranic principle that states that human sight cannot comprehend God. ‘No human vision can encompass Him, whereas He encompasses all human vision’ (6:103). And if God is to speak to a human, it is not face to face, according to the Quran. ‘And it is not given to mortal man that God should speak unto him otherwise than through sudden inspiration, or [by a voice, as it were,] from behind a veil, or by sending an apostle to reveal, by His leave, whatever He wills [to reveal]’ (42:51). Here, the Quran has more authority in matters of faith than ahad hadith. • أخرج البخاري عن ابن عمر قال: وقف النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم على قليب بدر فقال: (هل وجدتم ما وعد ربكم حقا)، ثم قال: إنهم الآن يسمعون ما أقول. فذكرت لعائشة فقالت: إنما قال النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم إنهم ليعلمون الآن أن ما كنت أقول لهم حق … وروي أن عائشة احتجت بقوله تعالى (وما أنت بمسمع من في القبور) – فاطر 22. Here, Aisha is resorting to a Quranic verse in addition to ‘reason’ to reject a narration that implies that the Prophet, peace be upon him, was talking to the disbelievers who were buried in Badr. Aisha’s perspective was that the Quran was clear when it stated: ‘thou canst not make hear such as are the dead in their graves’ (35:22). Discussion Aisha’s method outlined above is not unique in the history of the Islamic legal theory. Imam Malik, for one example, rejected the (authentic) narration of washing your plate seven times if a dog drinks from it based on the verse that states: ‘They will ask thee as to what is lawful to them. Say: “Lawful to you are all the good things of life.” And as for those hunting dogs which you train.’ (5:4). Ibn Rushd, for another example, rejected the (authentic) narration of ‘killing black dogs’ based on the Quranic and Prophetic principles of being kind to animals and not to transgress against living beings. And so on. In today’s scholarship, the criteria that Aisha utilised to critique hadith could apply to some hadiths that have significance. In such cases, although the hadith are authentically chained, in terms of their sanad, they do contradict some Quranic principles in terms of their matn. Sheikh Taha Al-Alwani rejected the authenticity and/or the common understanding of the narration, ‘Whoever changes his religion, kill him,’ based on its contradiction to the principle verse, ‘no compulsion in matters of faith’ (2:256). Sheikh Mohammad Abu Zahra rejected the authenticity and/or the common understanding of the narrations of ‘stoning the adulterer’ (rajm al-zani) based on the general principles of mercy in the Quran in addition to the verse that prescribed ‘half of the punishment’ in some cases (and ‘stoning cannot be divided in half’, he said). Sheikh Al-Ghazali rejected the authenticity and/or the common understanding of the narration, ‘a people who entitle their affairs to a woman will never be successful,’ based on its contradiction with a number of verses and other narrations that support the juridical principle of equality of men and women. Sheikh Al-Ghazali also rejected the authentication of Sheikh Nasser Al-Albani to such hadiths as, ‘there is disease in cow meat’, and ‘do not travel by sea’, based on their contradiction with Quranic verses such as, ‘And likewise they declare as unlawful either of the two sexes of camels and of cows. Ask [them]: “Is it the two males that He has forbidden, or the two females …’ (6:144), and ‘And His are the lofty ships that sail like [floating] mountains through the seas. Which, then, of your Sustainer’s powers can you disavow?’ (55:24-25). In conclusion, the methodology that Aisha, may Allah be pleased with her, has followed in the examination and critique of the matn of ahad hadith, even they were claimed to be authentically transmitted, is needed for today’s projects of renewal in the Islamic law in order to align the details of the law to its firmly based principles of justice, mercy, wisdom, or common good.